June of 1992 saw the release of Tim Burton’s Batman Returns, sequel to the highly successful Batman released three years prior. Capitalizing on the popularity of their new icon, Warner Bros. set in motion creation of an animated series set in a similarly dark Gotham City that was aired weekday afternoons (Tonks). The series was a hit and the studio chose to run a feature film in theatres Christmas of 1993. Mask of the Phantasm was headed by the same creative minds of the weekday television show including directors Bruce Timm and Eric Radomski, writers Paul Dini and Alan Burnett, and composer Shirley Walker. This essay will discuss Walker’s use of thematic layers and identifying orchestration within her score for Mask of the Phantasm.

The larger budget provided by Warner Bros. for Mask of the Phantasm allowed for Walker’s musical resources to triple to what she had averaged on the television series (Takis). With her 110-piece orchestra, synths, and 25-member choral force Walker composes a wall-to-wall score to compliment the films compelling 70-minute animated storyline. To occupy the near 65 minutes of music Walker employs an economical and engaging compositional method which John Takis calls the “multi-layered” approach.

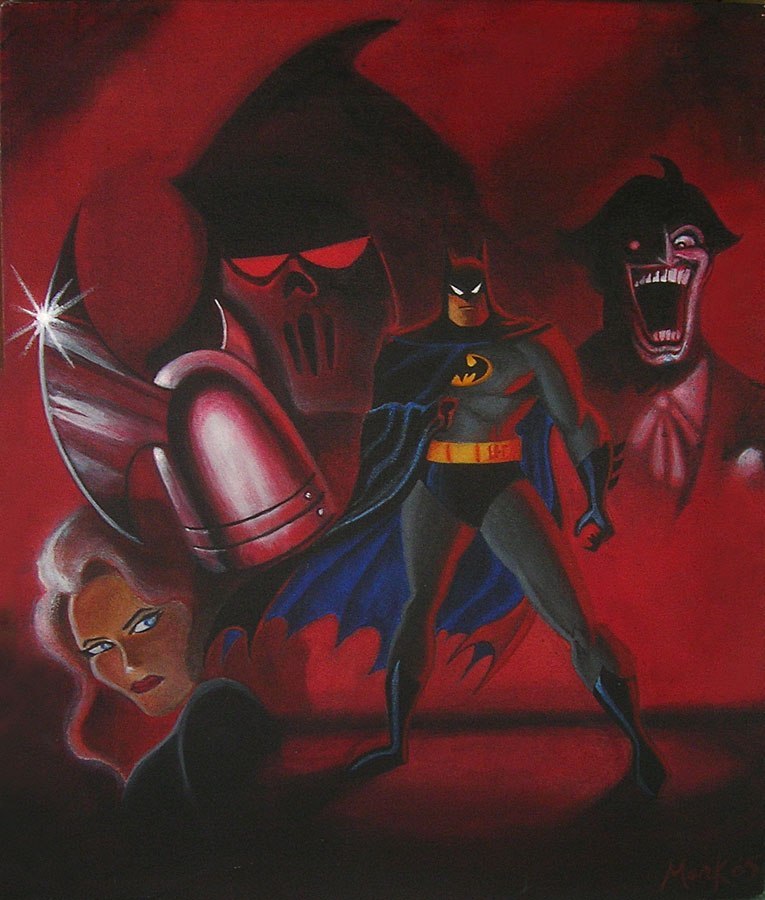

Walker composes seven themes using this multi-layered approach. They represent the characters of “Batman”, the “Phantasm”, “Joker”, “The Ski-Mask Vigilante” and the “Mob/Gangsters”. The two remaining themes represent Bruce and Andrea’s relationship; “Love Theme”, and Bruce’s vow of vengeance for his parents deaths; “The Promise”. Within all of these themes the chords, rhythm, countermelodies, and melody are all used not only simultaneously, but each separate element becomes an identifying component. (Takis)

Walker’s Batman theme is featured in the opening credits in a full choir and orchestral setting. As Walker explains in her demo-tape for the theme, presented in La-La Land’s 2CD release of music from the series, the theme is comprised of four elements; a main ascending call, two differing answers, and a transitional, climbing extension (Walker). The theme a crossover from her work on the animated series is first attached in the film to Batman when the Dark Knight swoops through the window to break up a Mob money-laundering racket. It is a four-note ascent using the three intervals of a minor chord. The first type of answer Walker describes as “dark and somber” and can be heard singularly when Batman investigates Sal Valestra’s apartment. The other “lifting and heroic” is most clearly presented in the final scene as Batman answers the call to duty as the Bat-signal shines in the Gotham sky. With the exception of the Main Titles both answers are best heard while Batman first dawns the cape and cowl. The climbing extension is different then her material she describes in here demo-tape. Rather then the modulating 4-note ascent as she describes in her demo-tape Walker uses a simple ascending scale line. The material she uses to both open and close the Main Tiltes and it is used again most clearly as Batman pursues the Joker in the last battle. Walker uses each layer of the theme throughout the film to different dramatic end but its association with Batman remains consistent.

Another example of Walker’s multi-layered theme is the “Phantasm” theme. It first appears during the character’s entrance in the opening parking garage fight. The theme can be broken down into two main parts. The first is the ghoulish melody, most often presented on theremin by future Batman composer Hans Zimmer. It’s otherworldly quality comments on the strangeness of the new masked assassin. The other element is the four chords that underpin the melody. The chords outer voices move chromatically toward each other for the first two chords then proceed away on the remaining two chords. To identify moments where the Phantasm exploits are involved Walker uses these elements layered together or separately. The melody is used alone just before Mob member Buzz Bronski is slain. The Phantasm doesn’t appear on screen but a solo flute plays the melody as the unsuspecting Bronski gropes for his surrounding in a dug out grave. The four underpinning chords are heard apart from the melody as the Phantasm and it’s foggy trail enter Mob member Sal Valestra’s apartment, and highlighted most clearly just before the apocalyptic explosions of the Gotham World’s Fairgrounds. Walker uses both elements separately to gain variety in the way she identifies the character.

Walker’s multi-layered approach to using themes in the film is heightened by her orchestration. As with the theremin’s presence reminding us of its attachment with the Phantasm other instruments help the audience to identify Walker’s “Mob/Gangster” and “Love Theme”. March-like rhythms in the low-reeds, stopped cymbal clashes, and muted brass help to identify the Gotham mafia and their gangsters. The muted brass harkens back to the early film scores and their use of jazz to represent the seditious subculture of the 1940’s and 50’s. The first encounter with the “Mob/Gangster” is heard during Bruce Wayne’s first night as defender of justice. His fight and chase with a gangster ring highlights the march-like rhythms and cymbals that connect the audience to the criminal’s identifying music. Making the distinction more evident is the presence of another theme representing Bruce, “The Masked Vigilante”. This variation of “The Promise” material is scored in a less menacing color, with sweeping string lines and heroic horn and trumpet melodies. Throughout the rest of the film whenever a Mob member is present Walker recalls the dark orchestral jazz tints, additionally employing a four-chord progression. The chromatic contour of the outer voices is an inverse of that of the “Phantasm” theme. Scored in the low-reeds Walker musically discloses a connection between the Phantasm and the Mob that the story will not reveal until its final scenes.

Orchestration also helps to identify Bruce and Andrea’s relationship in the “Love Theme” whether the theme’s melody is present or not. The theme is first heard in a flashback during a date to the Gotham World’s Fair. The melody, sung by a solo oboe and solo clarinet, speak of the intimacy of their relationship. Moving string lines, glockenspiels, and a dream-like synth generated tones and bells call to memory the optimistic moments between the two young lovers. The lighter orchestration appears without the melody in several subsequent scenes, most subtly in Andrea’s final scene. As Andrea broods on a distant cruise ship chords from the “Love Theme” sound, set in the high range of the violins, then seem to disappear with a passing sea breeze.

Walker’s two remaining themes are the “Joker” theme and “The Promise”. The “Joker” theme is the second carryover from her work on the television series into Mask of the Phantasm. It always accompanies the sadistic Clown Prince of Crime and is highlighted during the fight between the Joker and Batman in the Gotham of the Future scale model. The music is orchestrated with xylophones, vibraphones, woodblock, and playful clarinet melodies reminiscent of 70’s game show music. “The Promise”, associated with Bruce’s vow to avenge his murdered parents, is highlighted in the three major scenes in the film. In its occurrences the music is the major driving force in the narrative, neither dialogue nor sound effects overpower the score. The first full sounding arises as Bruce looks silently onto the portrait of his murdered parents. Here the solo trumpet takes the lead on the ascending chromatic melody with full legato orchestral backing. A solo trumpet again takes lead after Andrea returns Bruce’s engagement ring. Backed with heavier brass and a rhythmic string countermelody “The Promise” connects a montage of the portrait of the murdered Wayne couple and the ascent into the Batcave as Bruce first dawns the Cape and Cowl. Its most powerful occurrence is after the final fight between all three main characters. As Batman is caught in the Joker’s explosives that are decimating the Gotham World’s Fairgrounds, an apocalyptic, full-voiced chorus and orchestra are released. As the ground below gives ways, Batman falls into the sewer pipes and is pulled into the nearby ocean where the drains released him and watches the destruction. Walker’s choice in using “The Promise” speaks of an angelic act by his parents as he is spared from death because of the vow he has maintained in their honor.

Shirley Walker considered her work for Mask of the Phantasm to be her Magnum Opus. (Larson) Walker’s use of thematic layers and identifying orchestration within her score for Mask of the Phantasm are a testament to her skill as a composer and their success in to aid in the film’s dramatic narrative. Although Disney’s The Lion King overshadowed the theatrical release of the film, its home video release was positive and the animated series continued to enjoy a successful run. Shirley Walker passed in 2006. Her music for the Batman animated mythos remains in popularity. Multiple recent album releases on the La-La Land label honor her talent, skill, and superb ability to write for film and television. Through all of Batman’s adventures on film, Walker’s score for Mask of the Phantasm remains to be one of the strongest musical representations of the Dark Knight.

references + sources

Larson, Randall. “Remembering Shirley Walker”. December 2006, Interview Summer 1998. http://www.mania.com/content_print.php?id=52977

Takis, John. “Music of the Knight, Parts 1 and 3”. Film Score Monthly Vol. 14 Iss. 4, 2009.

Tonks, Paul. “Batman: The Animated Series; A Celebration”. 2002. http://www.asitecalledfred.com/score/7a.html

Walker, Shirley. “Batman: The Animated Series. Volume One”. Prod. MV Gerhard. La-La Land Records, 2008.

Walker, Shirley. “Batman: Mask of the Phantasm. Expanded Archival Edition”. Prod. Thaxton. La-La Land Records, 2009.